Needlework, Love and Liberation

We explore the power of embroidery to unite those facing the most challenging of circumstances.

During the Second World War, an extraordinary woman named Mies Boissevain-van Lennep worked for the Dutch Resistance, helping Jewish refugees to escape Nazi Germany by concealing them and procuring false papers to assist their getaway. However, in 1943 Nazi officials raided the family’s home and discovered evidence of their covert activities. As a result, Boissevain-van Lennep lost everything and everyone dear to her; two of her sons were executed by firing squad, her husband and another son sent to Dachau concentration camp, and her daughter imprisoned in Holland. Alone, she was incarcerated at Ravensbruck concentration camp until its liberation in 1945.

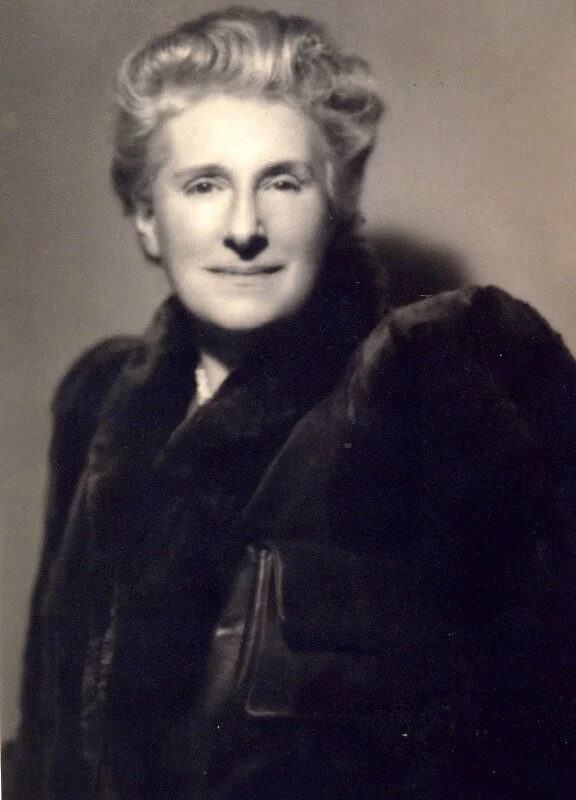

Mies Boissevain-van Lennep, courtesy of Jan Willem Boissevain

During her time at Ravensbruck, Mies had an incredibly poignant experience that led her to champion the power of textiles to heal and to forge communities. An extract of the speech Boissevain-van Lennep gave on the radio programme Woman to Woman in April 1946 provides insight into her experience within the infamous concentration camp and the incident that inspired the Liberation Skirt:

The cell was stifling and everything was ugly…stone…steel…frosted glass …Ugly, ugly, ugly. After fourteen days our laundry arrived… a moment of joy and expectation… But then comes the big surprise, at the bottom of the bag is a little patchwork-scarf! Little pieces of cloth, fresh, colourful and bright. Cloth that I remember from my children’s dresses and gowns, beautifully composed by someone who loves me… All my cell-mates pick it up, admire it. faces light up. Suddenly there is colour in our bare cell existence. We hang the scarf over the ugly mirror… Its memory…remained. Not just of the scarf but of the lovely world it came from that was included in it’ (Boissevain-van Lennep in Jolande, 1994:302).

A dear friend of the resistance fighter had managed to smuggle this beloved gift into the camp, bringing with it a reminder of Boissevain-van Lennep’s previous existence, of her life before imprisonment and unimaginable loss. As she began to share the stories the scarf contained with her cellmates, ‘my relatives and friends came back to me. I talked and talked and my cell-mates became friends. Everything changed…”.

This touching reflection exemplifies the power of needle and thread to reinstate identity, return the past to us, and forge solidarity in the present.

Upon the liberation of Ravensbruck, Boissevain-van Lennep, one amongst millions, collected the fragments of her life. The patchwork scarf was her most sacred possession. Like every other female survivor, she was expected to return to her prewar existence, silently forsaking the woman that years of resistance, heartbreak, hard labour and malnutrition had shaped her into.

Millions of women like Boissevain-van Lennep, who had undertaken vital roles during the conflict, found themselves forced back into the domestic sphere, despite considering the nature of their gender fundamentally changed, and believing that their political and social identities would shift to mirror this. As we know, these women were sorely disappointed. Society expected them to return to their previous occupations, performing the unseen and unappreciated labour that had previously been their domain. During the course of the war, these women became engineers, mechanics, pilots and nurses, exploring and pushing the socially constructed boundaries of their gender. Now, the kitchen door was shut firmly behind them, their pinafores returned. Thoughts of aeromechanics begrudgingly replaced with shortcrust pastry, stubborn stain removal, and the dreaded mending pile.

Luckily, resistance still flowed through Boissevain-van Lennep’s veins- the mending pile sat untouched. Her scarf around her neck, she reflected upon its power to salvage her faltering sense of identity amongst the most hopeless of circumstances and to forge vital friendships that ensured her survival. And thus, the National Liberation Skirt was born, as artist and academic Clare Hunter puts it ‘as a rallying cry to women to…demonstrate their changing identity’, and to do this together.

Mies Boissevain-van Lennep, Textile Research Centre

This skirt, which was sewn from the material and emotional fragments of their previous lives, was intended as a physical manifestation of the war-altered consciousness of Dutch women, and the bravery, determination and unity they had displayed. In so doing, the National Liberation Skirt also had political aspirations. Clare Hunter believes that Boissevain-van Lennep hoped that the widespread showcasing of the skirt would ‘publicly demonstrate the courage, resolve and solidarity of Dutch women… and their right to play a part in forging [Holland’s] future,’. Within the skirt women found a means by which to rediscover and implement the self-expression and autonomy quashed by the Nazi regime; the act of creation enabled them to play an active part in the portrayal of both a personal and political identity.

Selvedge Magazine

It is obvious that women relished the political power and sense of camaraderie the National Liberation skirt provided. This is evidenced by photographs of women proudly wearing their skirts, and by the songs they wrote. The perception of the skirt as a successful means of negotiating trauma and rediscovering identity is particularly pertinent in ‘The Hymn of the National Celebration Skirt’, which was sung as women, clad in their skirts, marched past the houses of parliament in 1948:

Shape by your skirt a together-connectedness, Unite multiple forms, colours and lines;

In the stream of historical events Embroider the design with your heart and your hand.

Stamp your skirt with the mark of your days, Colour your flag with what Was and Will Be; The Present, the Past- merrily borne,

Let them adorn your costume, your family, your life.

Atria

The lyrics of this song speak not only of the effects of wearing the skirt, but of creating it. The ‘together-connectedness’ referenced was a vital part of Boissevain-van Lennep’s decision to tackle women’s lost identities through the medium of textiles. In this she was inspired by the quilting tradition of America, wherein women gathered to both create and communicate. By sitting around their stitched skirts and sharing the stories of the material fragments they were made from, Boissevain-van Lennep believed that solidarity and empathy could be realised. She hoped that sewing this skirt would act as a therapy substitute, which she termed grief work. In so doing, she recognised the potential of the needle as a tool of personal and communal healing, a potential that is at the core of Sabbara’s work.

The experience of the artisans we work with attests to the power of Boissevain-van Lennep’s vision and insight regarding the power of needle and thread. Through this power, Sabbara’s artisans forge new communities, process their experiences, discover independence, and just like Boissevain-van Lennep, find a way forward, together.

Sisterhood of the Stitch blog series by Tashy Hughes.

References:

Hunter, C. (2019) Threads of Life. Hodder & Stoughton Ltd.

Jolande, W. (1994) Patchwork politics in the Netherlands, 1946-50 Women’s History Review.

Syrian cushions

Our hand-embroidered cushions are works of beauty that support refugee women.