The Quilt Makers of Changi Prison Camp

How female Prisoners of War interred by the Japanese in World War II used quilt making to send coded messages to their loved ones, and to create a world of freedom and beauty in the midst of suffering.

‘Changi Hotel’ signed Florence Jordan. Perhaps ‘hotel’ is a little joke meant to reassure her loved ones that she was not suffering too much?

When Singapore was taken by Japanese forces on February 15th 1942, during the course of the Second World War, five hundred women and girls were interred in the notorious Changi Prison Camp. Here they were separated from their husbands, sons and brothers, who were held in the male camp, and whom they would not see again until the end of the war in 1945.

The dehumanising conditions these women experienced are difficult to imagine. They faced severe overcrowding, malnutrition, and torture.

Many were colonial wives used to days of tea parties, afternoon rests and ex-pat gossip. Textile artist and academic Clare Hunter (who wrote beautifully about the Changi quilts in her 2019 book Threads of Life, which this blog is inspired by), argues that for these women, worse even than the physical trials was the uncertainty that plagued their every waking moment. Years spent chasing the mirage of hope. Would they survive to see their beloved homeland once more? What treatment were their sons and husbands facing in the adjoining camp? Would they be standing alongside them if freedom ever came?

In a bid to remedy the last and most painful of these fears, one of the women had an ingenious idea. Canadian prisoner and former Red Cross ambulance driver Ethel Mulvany proposed her solution, that oft-overlooked and underestimated female pastime: sewing. The height of incongruity within Changi’s unscalable walls, but all the more effective for this. Mulvany believed that the imprisoned women could utilise sewing’s virtuous reputation to their advantage, by using the medium to establish contact with their loved ones imprisoned within the male camp, and to assure them of their continued survival.

Mulvany’s plan was quietly ingenious. The women would create three quilts as gifts to the three Red Cross organisations active in Singapore – an Australian quilt, a British quilt, and a Japanese quilt (included as the ultimate decoy). They would present these quilts as humanitarian gifts for the patients of the male camp’s hospital, in so doing painting themselves as models of womanly virtue, while secretly sending coded messages of hope to their loved ones.

GR (George Rex) picked out in forget-me-nots (a well-chosen flower) and signed M. Broadbent. British nurse Maud Broadbent and her husband were living in Singapore at the outbreak of war, and he was interred in the male camp.

The letters IMNS in the bottom corner might be a clue to her role with the Malayan nursing service.

Just like their chosen craft, they were underestimated. Their captors were entirely taken in by their charade of female devotion, to the extent that – as Hunter shares with incredulity – Mulvany was for a time allowed to escape the confines of the camp once a month (under strict supervision) to buy sewing supplies from the market.

Mulvany implored the women to ‘sew something of themselves’ along with their signature into their allocated square, a space of six inches within which they could soar from the camp and revisit their old selves, savouring old delights and capturing them in thread for their beloved to feast on. The knowledge of their continued survival ensured by the evocation of shared memories on tattered cloth. Mulvany’s accomplices were only too happy to follow her instructions, as demonstrated by the Changi quilts which each contain sixty-six squares bearing the initials and personal symbols of the women who embroidered them.

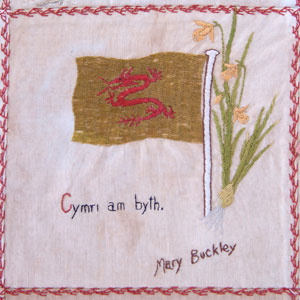

Mary Buckley was a Welsh nurse in Singapore before the war. You can see symbols of Wales on her square – daffodils, a red dragon, and the caption ‘Cymru am byth’ (Wales forever).

Clare Hunter is lucky enough to have seen one of the surviving Changi quilts in person when she visited the headquarters of the British Red Cross in London, where it is displayed. During this visit, she was initially bewildered by the cream squares that absorbed her. She did not expect this artefact of war to express the ‘frivolity of femininity’. She had imagined a textile weighed down by the suffering with which it was wrought. Instead, she encountered a thing of beauty, colour, and most shockingly, of life. Butterflies traverse the quilt, ships sail across its oceans, poppies and primroses burst from its earth, lambs bleat, cherries hang heavy in their ripeness.

We may ask where such idealised visions of home belonged amongst the squalor of the camp, how its inhabitants, worn down as they were by the grind of daily and prolonged suffering, could even imagine, yet alone bear to illustrate, the beauty of a home they feared they would never see again. Absorbing the scenes upon this quilt, Hunter came to see these motifs for what they truly were. In her own words: ‘trapped in the squalor of the camp, surrounded by the uncertainty of survival, these women embroidered motifs that symbolised what most sustained them. They stitched patriotism, hope, defiance, and love.’

This observation provides key insight into why the practice of embroidery was so vital to sustaining these women’s collective and individual spirits. More than just showing their loved ones that despite all they lived on, the very act of sewing – immortalising their existence through thread – demonstrated this unequivocal fact to the women themselves. Through each stitch they reformed themselves anew and reminded themselves of the beauty that existed beyond the prison’s walls and their promised place within it once they escaped them.

Nurse Elizabeth Burnham and her husband were British. You can see she has sewn the date she entered the prison, followed by a question mark – she didn’t know when or if she would ever leave. Or perhaps it is a signal to her husband that the day of freedom will indeed come at some unknown time.

The sustaining powers of embroidery, so crucial to the women of Changi prison camp, are also evident in the work of Sabbara’s artisans. As Hunter so shrewdly perceives, sewing’s physicality, ‘the making of something substantial from discarded remnants, is a comforting metaphor for personal growth in the face of an enforced reduction’. Through their work, Sabbara’s artisans make beauty from loss, embedding each stitch with the pain it took to leave their home, their life, and emerge anew, even stronger than before.

Sewing is the ultimate remedy for helplessness: those who ply the needle can travel through its eye and into a world where they are the author of their own destiny, where they can create beauty, colour and life, and immerse themselves within it.

For more information about the Changi quilt held by the British Red Cross, see https://changi.redcross.org.uk/

Sisterhood of the Stitch blog series by Tashy Hughes.

References

Hunter, C (2019). Threads of Life, A History of the World through the Eye of a Needle, Sceptre.